Random Walks in Products of Free Groups

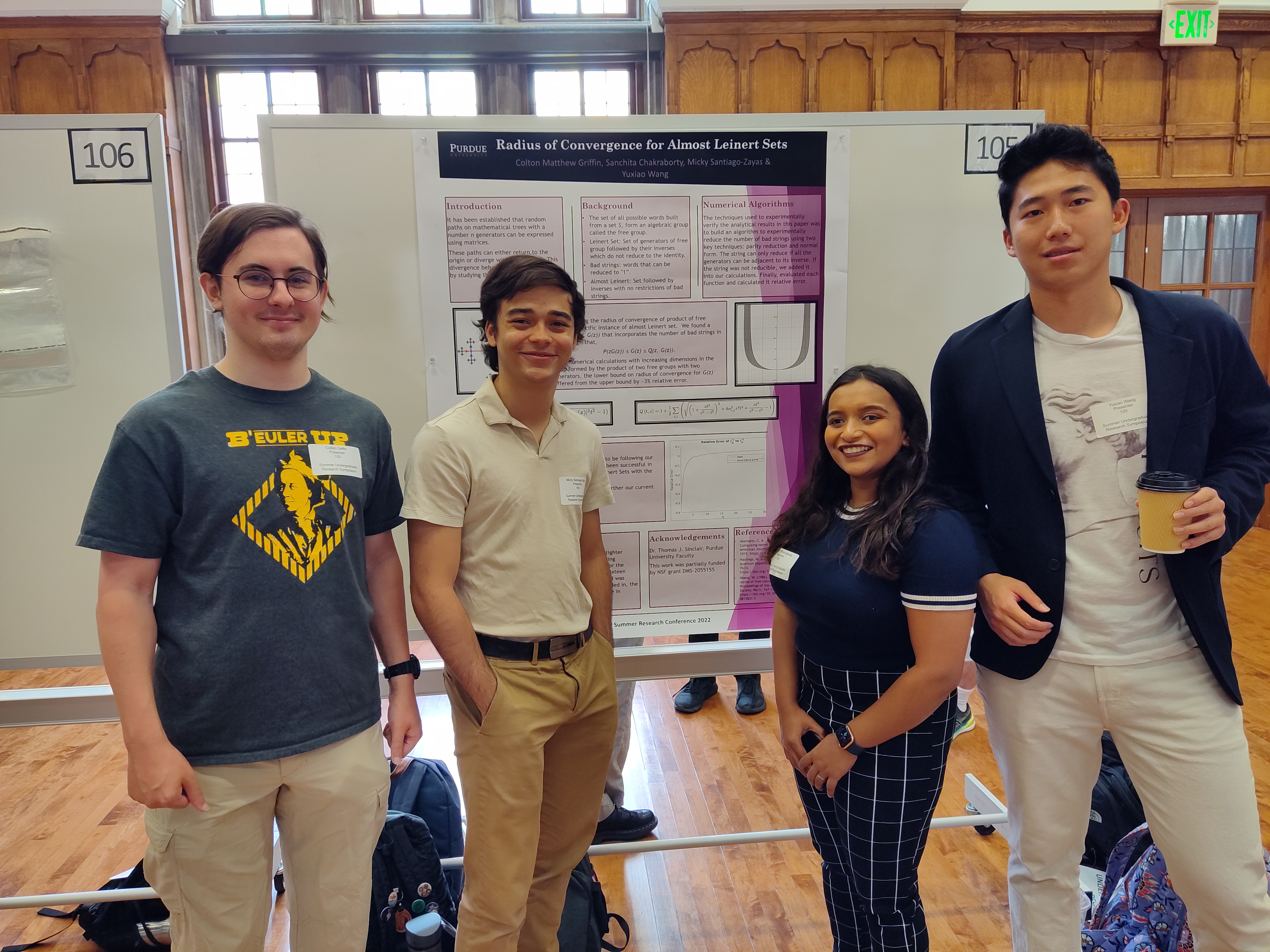

Last night, on April 20th 2023, I had the opportunity to share with the Department of Mathematics at Purdue University some of the ideas I worked on during the previous Summer 2022 with Dr. Thomas Sinclair and other peers in the field, Colton Griffin, Sanchita Chakraborty, and Yuxiao Wang. I will try to summarize the presentation, as well as our preliminary results from when we worked on the project.

Purpose

The main goal was to explain the underlying concepts of the study in a brief 10 minute presentation to a wide audience without feeling limited or confused by the complexity of notation and the mathematics used.

Introduction

Groups

Firstly, we refreshed the concepts of groups in abstract algebra. Most importantly, we must remember that the main properties of groups are:

- an operation that allows pairs of elements to interact

- an identity element exists

- the existence of inverse elements

For example, the integers modulo n groups has the addition operation, 0 as the identity element and every non-zero element in the set has an element which added to itself returns to zero, e.g.,

I am intentionally utilizing the modulo group as it is also a special case of groups, an abelian group. Abelian groups are special because the results are independent of the order in which the operation is done, i.e., it possesses the commutative property. However, our study focuses in a group that does not have the commutative property, free groups.

Free Groups

Group Properties

The elements in Free Groups are strings or sequence of directions taken (paths) from an origin, and these do not promise to be abelian, i.e., it is generally non-commutative. We can represent the group to be geometric so that the elements represent possible directions of movement. More specifically, we have an identity element, which we denote as e, representing the origin which happens by not moving. In this group, the operation is concatenation, this way, we can interpret the string generated from the operation to represent a history of movements starting from the origin. Every direction has an inverse direction, thus satisfying all the requirements. Most importantly, free groups, although non-abelian, are a special group, this is because they possess finitely many generator elements, the same way I intentionally snuck the integers modulo n example. These special elements generate all other possible elements in the group. This way we can interpret visually two cases: the commutative and the non-commutative, even though they have the same number of generators, for example, up and right direction elements.

Examples of Two Generators

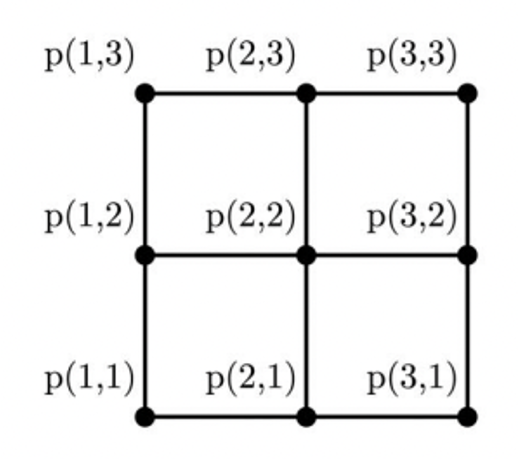

- In the commutative case, consider the image below which is just a simple cartesian grid. If we consider

(2, 2)to be the origin, right up is equivalent to up right, i.e.,(3, 3).

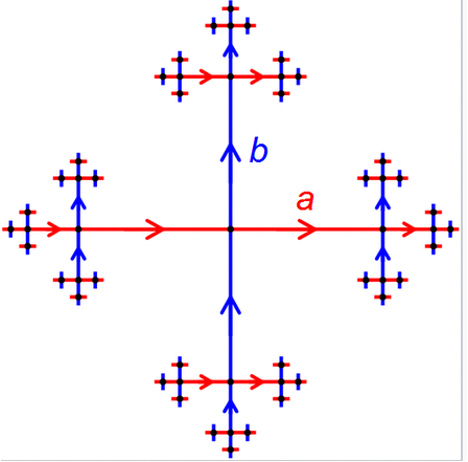

- On the other hand, a non-commutative case would be the Cayley graph underneath which is more analogous to free groups. Although we still have two generators a and b, being right and up respectively, like before but still the

abstring is not the same location asba.

Leinert Property

Informally, we can express the Leinert property to be a very self-evident fact about the Free Groups. That is, the only way to return back to the origin with any given string is by undoing every step of the original string. In other words, for a given string, the only inverse string is to flip the elements so that the last element is the first and the first is the last, as well as inverting them to their group inverses. Namely, for

the string is first flipped left to right,

then, flip by inverting the elements, as follows,

I will let you try to convince yourself that

because

However, we can see that is not true in the commutative case as we can undo any step at any time so there is no unique inverse.

Definitions & Notation

-

The probability of moving in the direction n is denoted as

-

The probability of moving in direction inverse to n so that

is denoted as

-

The probability of staying in place is denoted as

-

The probability of returning to the origin after infinitely many steps, named the spectral norm, is given by the following equation,

Our study

Goal

We should mention first that Woess (1986) managed to prove that the spectral norm for the random walks in groups with the Leinert Property to be the inverse of the radius of convergence for the following function:

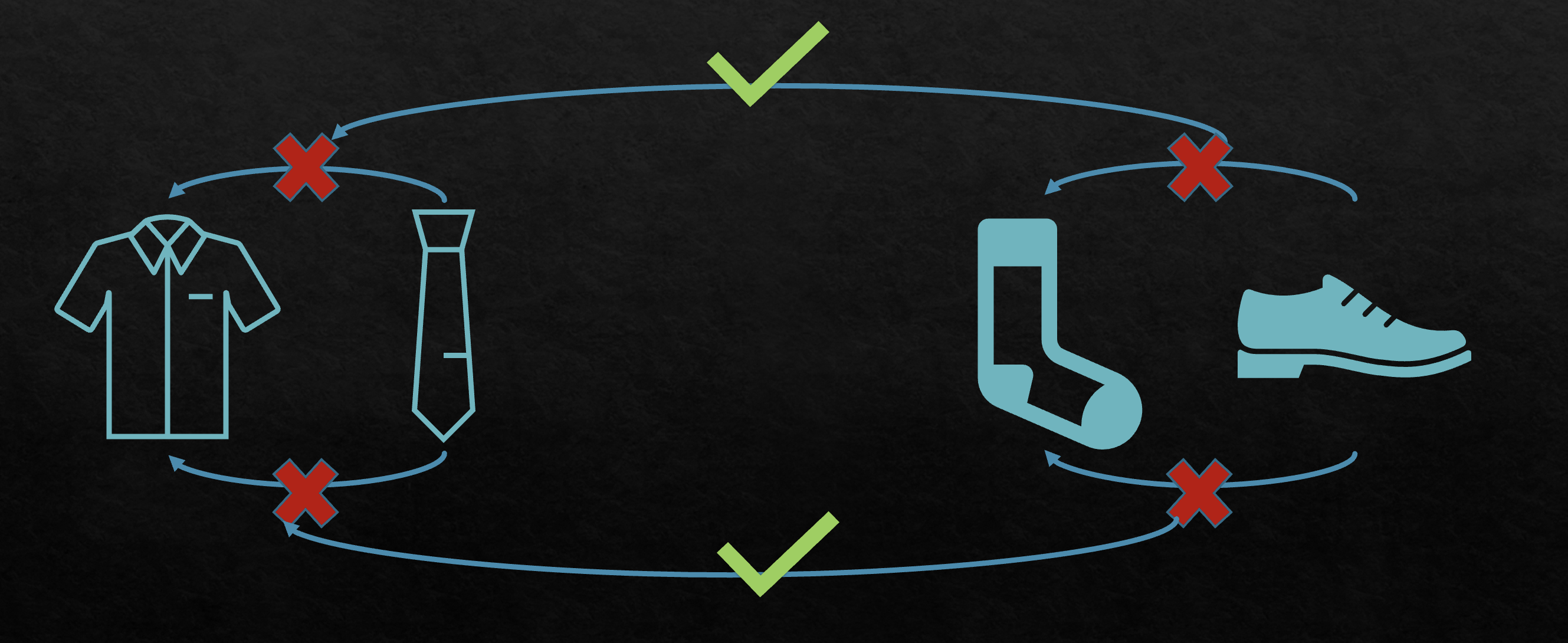

Is there a middle ground between the commutative and non-commutative case? Or let me better rephrase the question as, is there Almost-Leinert cases and how would these behave? Well, analogically, we can visuallize the problem with the following daily circumstance:

When dressing up, we are not able to change the order in which we dress the shirt and tie, or the socks and shoes. However, we still have the freedom to dress as, (sock, shirt, shoes, tie) or (sock, shoes, shirt, tie). It is sufficient to dress the shirt before the tie and the socks before the shoes, anything else is possible. So what might the spectral norm of groups which do not strictly follow the Leinert Property be? What is an example of such a case? Well, a good simple example is the product of free groups.

Imagine two free groups, both of containing two elements and an identity as follows:

As you can see, a,b and x, y are non-commutable amongst each other, however, a with xand y, b with xand y, and their converses, are. So fundamentally, our main goal is to find what the spectral norm is on these Almost-Leinert scenarios, however, for the purpose of our study, we focused on the product of free groups of the form

and its behavior as

n increases.

Methods

We had two main strategies and approaches, permutate the results made by Woess’ through rough approximation and analysis to find the rate of the probability to return to the identity element in the product of free groups scenario. In other words, finding an equation to evaluate the spectral norm of this new group and show an upper bound to the number of walks that do not return to the identity element a group has. Then, through counting, evaluate how close the perturbed equation to experimental cases of the product of free groups. We can simulate random walks in a computer through random matrices as mentioned in Hastings (2007), and to access our original code in the following Github repository were the main agorithms to our methods lie. We suspected that as the number of dimensions increased, the expected number of simplifiable strings (the resultant random unitary matrices), although correlated, can still be computed by finding an error term which can be done by altering the equation worked by Woess as mentioned above.

Results

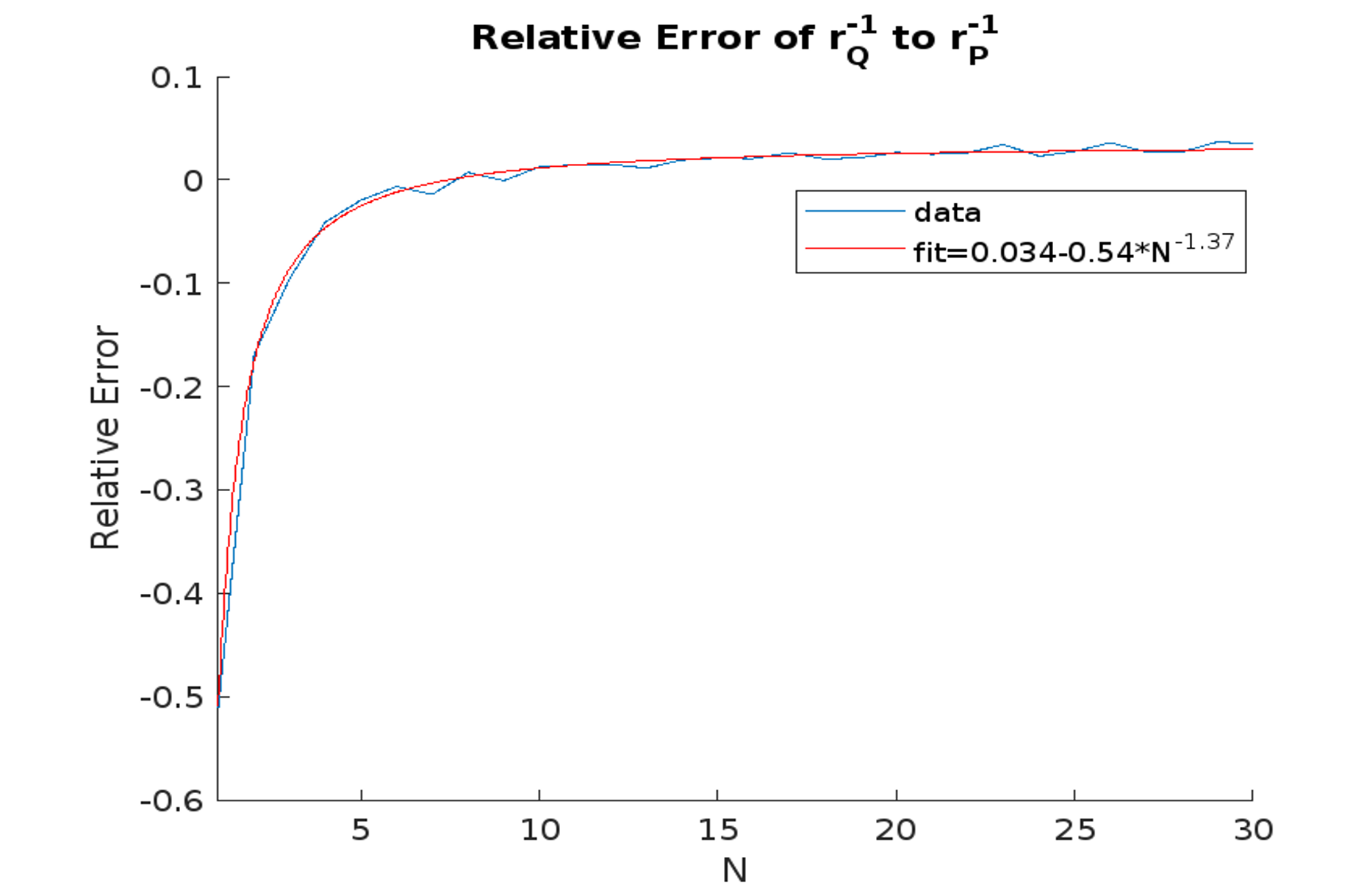

As some substantial results, we showed an upper bound to the number of bad walks. Also showed a perturbed equation of Woess with an error term for sets that have this Almost Leinert behavior. And numerically found that through our experimentation of random calculations, it was around 3% of relative error to the equation.

When studying the radius of convergence of product of free groups, we found a function Q(z, G(z)) that incorporates the number of bad strings in the set such that,

where

G(z) is the same representation from Woess. The functions are:

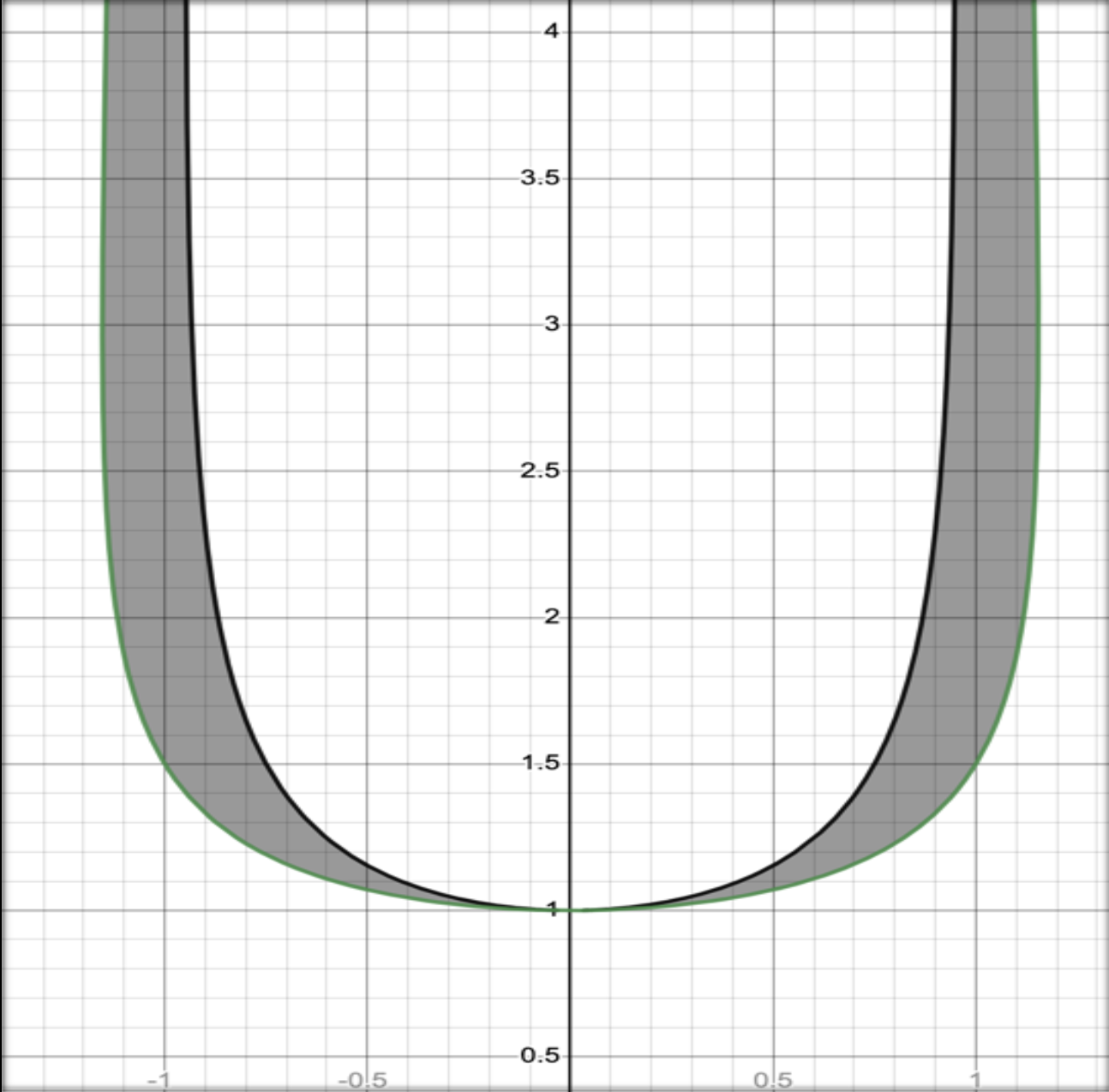

These equations when plotted behave as follows,

Our experimentation through our numerical calculations with increasing dimensions of matrices in the group formed by the product of two free groups with two generators, the lower bound on radius of convergence for G(z) differed from the upper bound by about 3% relative error as shown in the plot below.

Conclusion

Although our results are still inconclusive, results seem to be following our intuition created by past studies. This new function has been successful in tightly bounding the radius of convergence of almost Leinert Sets with the radius of convergence found by Woess for Leinert Sets.

Further calculations and analysis must be conducted to further our current understanding over the topic.

Takeaways and Future Directions

Future works should consider analytically exploring a tighter bound on the "irreducible" strings (strings that do not simplify to the identity) as the size of the string exponentially decrease in proportion to valid strings. For the purposes of this project, only bad strings up to length sixteen, and the minimum length of the string found was length 8. As the length increases and bad strings are added in, the number of bad strings are seen to exponentially increase in proportion to valid strings. However, we have no numerical approximation to determine the growth of these bad strings. There is also no complete reasoning for why this altered recurence bounds the equation tightly.

There was also an interesting observation during our study, that is, the x coordinate of the tangent at the bulge point for the plot generated from Q, as shown in the plot above, is always less than the reciprocal of c. There is missing reasoning for why this is true, however, our team suspects it has to do with the fact that the x coordinate of the tangent for P occurs at the reciprocal of the radius of convergence of G as discussed by Woess.

References

Additional information

- The slides used for the short presentation at the Presentation Night.

- The poster used for the Purdue Summer Undergraduate Research Poster Symposium and Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) Research Conference of Summer 2022.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Thomas Sinclair for his support of the team and allowing me to be a part of such an exciting experience and being an incredible mentor/teacher for both the Presentation Night and the study's development. My team members, Colton, Sanchita and Yuxiao for being an incredible team with insightful ideas and discussions. In addition to Dr. Jonathan Peterson for hosting and organizing such an incredible and insightful event. Also, Dr. Ignacio Camarillo, director of LSAMP, for teaching, organizing, and funding my personal involvement in the project. I would also thank the National Science Foundation for funding Dr. Sinclair's work, having our work partially funded by the grant DMS-2055155. Lastly, I would like to thank the audience for the attention throughout the presentation and the engagement received in the QA section. I really appreciated all the opportunities I was granted and will forever be in debt to all of you as I thank you all for making my first research experience in academia one I could never forget.

Leave a Comment